Health Care Sheds 43,000 Jobs in March, the Biggest Loss in at Least Three Decades

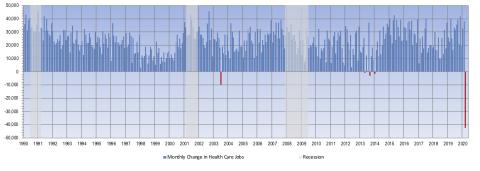

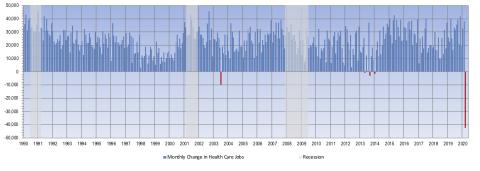

Today’s jobs report begins to reveal the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on employment. More than 700,000 jobs were lost since February. But the world has changed even in the three weeks since these data were collected (second week of March), and the end of this story is not yet in sight. As the chart below illustrates, the loss of 43,000 health care jobs in the first month of the COVID-19 economic downturn is unlike anything we have seen at the start of a recession over the past three decades.

Month-over-month change in health care employment, 1990 through March 2020

(Monthly losses shown in red)

Health care has traditionally cushioned the blow of non-health sector job losses during and immediately following economic downturns. As we and others observed, job losses during the Great Recession would have been larger had health care employment not continued to grow. By 2010, there were 8.6 million fewer jobs than at the end of 2007 when the recession began; the loss would have been 9.2 million had health care not added nearly 600 thousand jobs. It took until November 2014 (fully 65 months into the economic expansion) for non-health jobs to return to their pre-recession level, at which point health care had grown by 1.7 million jobs.

This time, health care looks to be contributing to instead of counterbalancing an accelerating economic calamity. Health care lost 43,000 jobs this month, by far the largest monthly drop in our data series going back to 1990. This may seem counterintuitive as we read daily of health care providers caring for COVID-19 patients stretched to capacity, but other types of health services have been shutting down like the rest of the service economy. This month’s losses were concentrated in ambulatory care settings, including physician offices, dental offices, and offices of other practitioners. As non-essential visits were cancelled, and states began ordering social distancing, such offices were closed. Even telemedicine visits, directly linking providers to patients, reduce the use of support staff.

Once things “return to normal,” demand for deferred health care may surge. But some routine care will never be made up and some conditions may resolve on their own. Indeed, care overall may be viewed differently as to what is required and what is discretionary. Like other service industries, health care providers are also suffering financial losses at a scale unlike in past recessions. The combination of intensive and costly COVID-19 care and the loss of high-margin discretionary procedures is devastating for hospital finances. While hospital jobs remained stable between February and March, even hospitals are beginning to furlough workers as revenues plummet and margins disappear.

Health care job growth during a recession is not necessarily a good thing in the long run, as it reflects more and more of our societal resources going to health care spending. Baicker and Chandra have argued that “employment in the health care sector should be neither a policy goal nor a metric of success.” Nevertheless, today’s jobs report gives us one more sign that this downturn is unique, and may be more painful than any in our lifetime.

Altarum’s health sector tracking work is made possible by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.